Asphalt Paves the Way

By American Oil & Gas Historical Society -- June 18, 2020A major theme of political economy is the undesigned order of the market under private ownership, voluntary exchange, and the rule of law. By permission from the American Oil & Gas Historical Society, MasterResource will publish articles documenting the progress of the market-driven U.S. energy industry. (This article was originally published by AOGS in 2014.)

American mobility would soon depend on a petroleum product from the bottom of the distillation process.

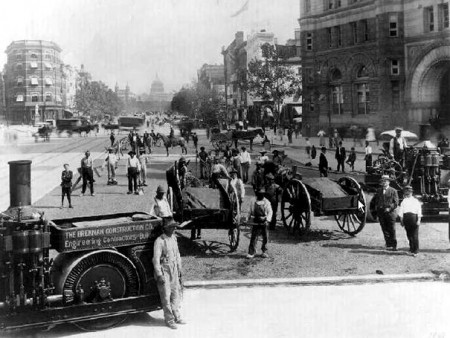

[Pennsylvania Avenue was first paved bitumen imported from Trinidad bitumen in 1876. Thirty-one years later, a better asphalt derived from petroleum distillation was used to repave the famed pathway to the Capitol, above.]

President Ulysses S. Grant directed that Pennsylvania Avenue be paved with Trinidad asphalt. By 1876, the president’s paving project covered about 54,000 square yards, according to A Century of Progress: The History of Hot Mix Asphalt, published in 1992 by National Asphalt Pavement Association.

“Brooms, lutes, squeegees and tampers were used in what was a highly labor intensive process. Only after the asphalt was dumped, spread, and smoothed by hand did the relatively sophisticated horse-drawn roller, and later the steam roller, move in to complete the job.”

Three decades later, the road to the Capitol was repaved with new and improved asphalt – made from petroleum. The abundance of asphalt makes it seem unremarkable, yet without this basic residue from the petroleum refining process, bad roads may well have delayed much of the nation’s economic progress of the 20th century. Ninety-four percent of U.S. roads and streets are asphalt – variously known as blacktop, tarmac, macadam, plant mix, asphalt concrete, bituminous concrete, and Hot Mix Asphalt.

[Asphalt left over from oil refining presented an alternative to imported bitumen.]

Since 1824, asphalt has paved more than two million miles of America’s roads, much of it with the 80 percent of asphalt that is recycled.

The domestic asphalt business began in 1595 with imports from a naturally occurring bitumen lake found on the island of Trinidad, just off the northern coast of South America. Sir Walter Raleigh first described the lake as a “plain” of asphalt and used it to re-caulk his ships.

Almost 300 years later, in 1875, President Ulysses S. Grant directed that Washington’s famed Pennsylvania Avenue be paved with Trinidad asphalt.

The use of asphalt left over from crude oil refining presented a readily available alternative to imported bitumen. This byproduct offered an economic means of dramatically improving roadways.

[The thousands of automobiles that began rolling off assembly lines after World War I needed more and better roads.]

By 1902, the Texas Gulf Refining and Texas Refining companies produced asphalt, as did the Sun Oil Co. in Pennsylvania. The next year, Congress established a mechanical and chemical laboratory to test road materials. Within a decade, petroleum asphalt dominated the marketplace.

The thousands of automobiles that began rolling off assembly lines after World War I needed more and better roads. Innovations in both producing and laying asphalt included mechanized spreaders and mixers – reducing, but never eliminating, manual labor.

Asphalt Paves U.S. Interstates

During World War II, runway surfaces had to handle larger and heavier loads, prompting innovation in asphalt composition and paving technology. Road building became a huge industry to accommodate America’s postwar boom.

[Missouri launches the U.S. interstate system after “inking a deal for work on U.S. Route 66 – now Interstate 44,” which stretches across south central Missouri and is a major corridor to the West Coast.]

Responding to public demand, Congress passed the State Highway Act and allotted $51 billion to the states for road construction.

The Highway-Aid Act of 1956 provided 90 percent federal funding for a “system of interstate and defense highways” — the Eisenhower administration noted a need to efficiently evacuate major cities in the event of a nuclear attack. The act made it possible for states to afford construction of the network of national limited-access highways, which will eventually reach more than 40,000 miles. In August 1956, Missouri became the first state to award a contract with the new interstate construction funds, “inking a deal for work on U.S. Route 66 – now Interstate 44 – in Laclede County,” noted the Missouri Department of Transportation.

“There is no question that the creation of the interstate highway system has been the most significant development in the history of transportation in the United States,” the state agency added. Advanced pavement materials now include compositions such as Open Graded Friction Course, and Stone Matrix Asphalt, better known as “Superpave.” By 2005, the Federal Highway Administration reported that 2,601,490 miles of U.S. roads were paved with a variety of bituminous surfaces.

Although asphalt comes from the bottom of the fractional distillation process, its contribution to America’s mobility makes it one of the petroleum industry’s most important products. Every day it passes largely unnoticed under millions of tires. Also see America on the Move.

Asphalt Drip Makes Science History

On July 11, 2013, physicists in at Trinity College Dublin photographed one of the most anticipated drips in science.

[Begun in 1927, another “Pitch Drop Experiment” continues in Australia today. Photo courtesy University of Queensland.]

“After 69 years, one of the longest-running laboratory investigations in the world has finally captured the fall of a drop of tar pitch on camera for the first time,” notes the science journal nature.

Considered one of the longest-running laboratory investigations in the world, the pitch-drop experiment was set up in 1944 to demonstrate the high viscosity or low fluidity of pitch — a naturally hydrocarbon also known as bitumen or asphalt.

An even older “Pitch Drop Experiment” in Australia, which began in 1927, continues. It missed filming its latest drop in 2000 because the camera was offline, notes writer Richard Johnston. It takes seven to 13 years for a drop to form – but only a tenth of a second for it to fall.

Both experiments demonstrate the high viscosity or low fluidity of pitch – also known as bitumen or asphalt – a material that appears to be solid at room temperature, but is in fact flowing, albeit extremely slowly,” he explains. The Trinity College team has estimated the viscosity of the pitch in the region of two million times more viscous than honey.

The Australian experiment has been running since 1927 at the University of Queensland in Brisbane, which Guinness World Records lists as the world’s longest-running laboratory experiment. The experiment has yielded eight drops, with the ninth drop now almost fully formed. It is expected to fall at any moment.

___________________________________________________________________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Support this AOGHS.org energy education website with a contribution today. For membership information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2019 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Asphalt Paves the Way.” Author: Aoghs.org Editors. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/products/asphalt-paves-the-way. Last Updated: December 15, 2019. Original Published Date: June 18, 2014.

[…] post Asphalt Paves the Way appeared first on Master […]

[…] Asphalt Paves the Way […]