“The Price Anderson Suicide Pact” (Devanny on nuclear power insurance reform)

By Robert Bradley Jr. -- March 26, 2024“Let’s be clear. Nuclear power’s Secondary Financial Protection is not insurance. Insurance is a voluntary agreement among the parties in which all or a portion of a risk is transferred from one party to another in return for a payment, which is set by the participants, ideally in a competitive market. The SFP is a government mandated protection racket.” (Devanny, below)

“The only solution is a fixed compensation scheme with each plant being responsible for its own liability insurance. If a compensation scheme, based only on the dose profile each individual and business would have incurred assuming no evacuation, is combined with a radiation-harm model that recognizes our bodies’ ability to repair radiation damage within limits, the risk will be easily insurable.” (Devanny, below)

The notorious Price-Anderson Act, enacted in 1957 as part of a federal effort to get peaceful atoms into commercial use, has been extended seven times and is set to expire on its own terms next year (end of 2025). Last week’s post by Kennedy Maize described the latest federal subsidies to keep nuclear afloat as a forward-looking industry.

At LinkedIn, Jack Devanny explored the in’s-and-out’s of Price-Anderson to ask: Is this subsidy really worth it to the regulated industry? How should nuclear liability be restructured in a more rational way? His analysis follows.

Not Deaths, Dollars are at Stake

In the US, the response to the next sizable nuclear power plant release will be governed by the Price Anderson Act and the American tort system. Under Price Anderson, any US nuclear power plant over 100 MWe must purchase liability insurance equal to “the maximum amount available at reasonable cost and on reasonable terms from private sources.” That amount is determined by the NRC, which just increased it to $500 million. This is called Primary Financial Protection.

There is a single provider of this insurance, American Nuclear Insurers (ANI), which lays off the risk to a consortium of underwriters at Lloyds and elsewhere. The annual per plant premium is roughly $1,000,000. Since there are about 70 such plants, a little more than 7 years of revenues covers the entire underwriters’ risk. It’s an extremely profitable arrangement. Over the last 50 plus years, The ANI consortium has paid out $150 million in claims, $71 million at TMI, while collecting over 4 billion dollars in premiums, and further profiting from the investment returns on that money.

In a normal market, sellers would be scrambling to do more of this business, pushing the price down. The non-life insurance market is very large, collecting over 2 trillion USD in premia in 2013. And in fact, underwriters estimate that ten to 15 billion dollars worth of coverage is available at a cost of 0.1 to 0.2 cents/kWh.\cite{wna-liab} So why does the NRC claim that only 500 million dollars is available at “reasonable cost”?1

One reason is that under Price Anderson the Primary Financial Protection is backed up by a Secondary Financial Protection (SFP). This is a post-casualty assessment on all US nuclear plants, each of which is liable up to $138 million per reactor per casualty, collectable in annual installments of $20 million. These numbers are periodically adjusted for inflation. Currently, the value of this pool is about $14 billion.

Let’s be clear. SFP is not insurance. Insurance is a voluntary agreement among the parties in which all or a portion of a risk is transferred from one party to another in return for a payment, which is set by the participants, ideally in a competitive market. The SFP is a government mandated protection racket. Youse want to stay in business, sign here or we burn the place down. Of course, the NRC need not resort to arson. It will simply yank your license. The people who will end up paying will be the utilities’ customers. There’s nothing voluntary about it.

When the next big US release occurs, $500 million won’t begin to cover the claims. The $14 billion won’t begin to cover the claims. The American tort system will see to that. After the Deepwater Horizon blow out, the ambulance chasers descended on the Florida Keys, where I was living. They held “seminars” at the fanciest hotels with plenty of free food and drink. These seminars instructed everybody store owners, bar owners, charter boat captains, fishing guides, how to make claims ….

Charter boat skippers were getting $100,000 checks for lost business. One Key West bar got $600,000. The oil spill never came within 700 miles of the Keys. If there was any lost business in the Keys (doubtful), it was due to grossly inflated and just plain inaccurate coverage of the spill. BP’s total bill ended up around $65 billion dollars. If the ambulance chasers can do this with an oil spill, can you imagine what they would do with radiation?

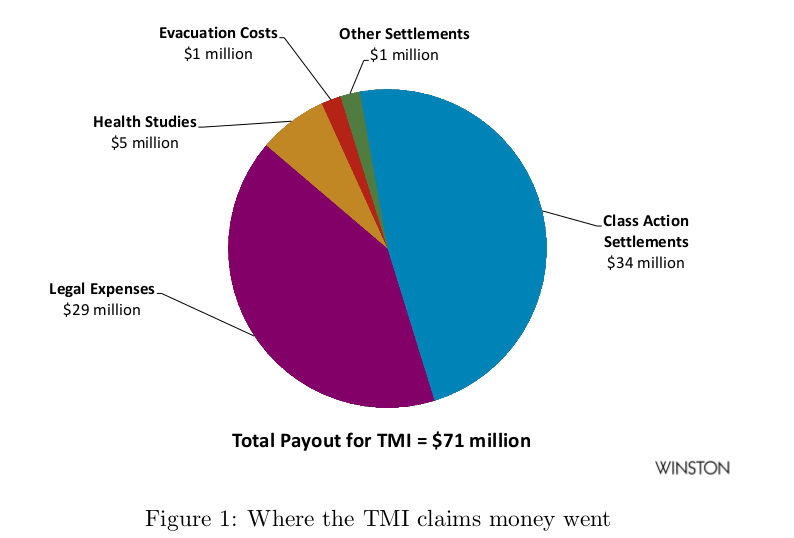

At Three Mile Island in 1979, the maximum individual dose to the public was 0.37 mSv, about the same as the additional dose he would have received by moving to Denver for a month. The paid claims totaled $71 million, but barely over 50% of the money went to the public, Figure 1.

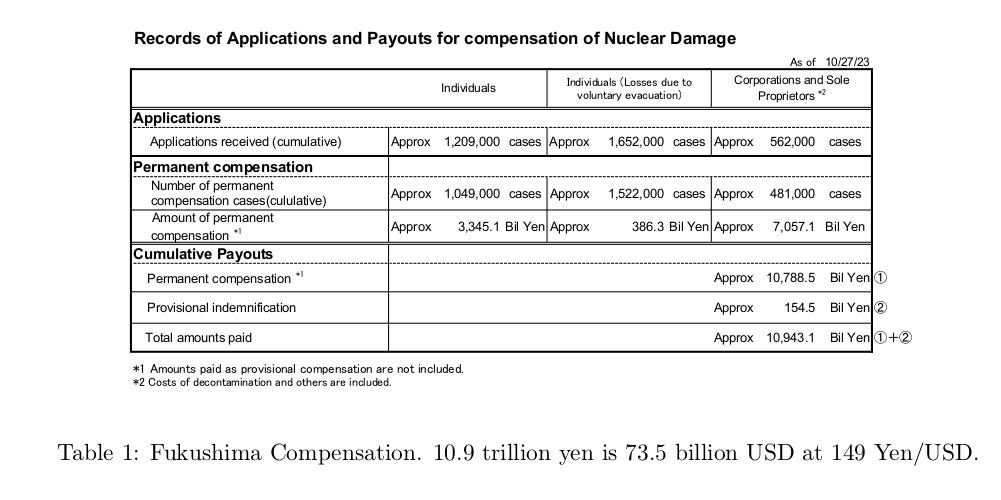

The Fukushima release was very roughly 100,000 times larger. It has produced no detectable radiation harm among the public, nor is any expected.\cite{unscear-2021} There was no need for any evacuation, certainly not evacuations lasting more than the time that it took to stop the releases. Yet the compensation bill is now over $73 billion, Table 1, in a country that has a far more disciplined tort system than the US.2

In both releases, there would have been no detectable radiation harm to the public without any evacuations. In both releases, essentially all the harm was caused by unnecessary evacuations, mandatory in the case of Fukushima, combined with nonsensical restrictions on return. At Fukushima, the mandatory evacuation area maxed out at 874 km2. After Fukushima, NRC Commission Chairman Jaczko said he would have evacuated everybody out to 50 miles (80 km), an area of more than 10,000 km2. The NRC would have increased the Fukushima trauma by more than an order of magnitude.

In a Fukushima-like release, American tort lawyers will blow through 14 billion dollars like a kid going through his weekly allowance. Price Anderson has some provisions that attempt to control the ambulance chasers. All claims go straight to the federal District Court for the district in which the casualty occurred. No jurisdiction shopping. All claims are channeled to the plant owner. The liability is no fault; and no punitive claims are allowed.

But the applicable law is the tort law of the state in which the release happened. And the jury will be made up of pissed off, scared, sympathetic neighbors (aka peers), most of whom will have a comic book view of radiation harm. If St. Lucie halfway up the Florida peninsula is the offending plant, the Keys bar owners and fishing captains will have a far stronger argument than they did after Deepwater Horizon, even if the plume comes nowhere near the Keys, as it almost certainly will not. In a Fukushima sized release in the US, we could easily see a trillion dollars in claims. No wonder a release is intolerable. It’s not the deaths; it’s the dollars.

Enter INPO

The Price Anderson Act responds to this factor of 200 difference between what’s said to be insurable and the potential claims by setting up an income transfer from all American nuclear power plant shareholders and ratepayers to the ambulance chasers and their plaintiffs. Price Anderson shackles all American nuclear plants together. Price Anderson is a mandatory suicide pact.

How does a plant protect itself from a sub-standard plant? The answer is INPO, the Institute of Nuclear Plant Operations. INPO was set up in 1979 after Three Mile Island revealed the danger. INPO is a self-regulation inspection service, a bit like the Classification Societies and the TUV’s. Without INPO approval, you almost certainly cannot get insurance. But there are three fundamental differences.

1) INPO is motivated not by the cost of actual harm, but by the cost of exceedingly unrealistic perceptions of radiation harm combined with the American tort system.

2) INPO is a creature of the plant owners, not the insurers. As a practical matter, INPO is controlled by the big nuclear utilities.

3) INPO is a monopoly. It does not have to compete with other INPO’s for customers.

(1) and (3) means there is no balancing mechanism between economy and preventing a release. Tasked with the job of preventing a trillion dollar claim, INPO has a monomaniacal focus on “safety culture”, which it defines as “an organization’s values and behaviors that serve to make nuclear safety the overriding priority.“[emphasis mine] INPO is based on the twin premises that a release is intolerable (on dollar grounds) and a proper safety culture can prevent that release. INPO is the latest embodiment of the Two Lies.

Regulatory compliance is not good enough. INPO often calls this “striving for excellence.” INPO inspects each plant about every two years. A team of 20 or more descends on the plant for about two weeks. Based on the report, INPO assigns a 1 to 5 score to the plant. Careers depend on that number. INPO sets up a rating competition among the plants. The cost of the electricity (and implicitly the harm from alternate sources) is given no weight in this rating. With INPO around, the NRC inspection process is superfluous.3

How does a plant demonstrate that safety is its overriding priority? By developing detailed procedures and extensively documenting those procedures and the plant’s adherence to those procedures. Over time, the competition to have the most detailed, best documented procedures results in an immense and ever growing paperwork burden.

The initial impact of INPO was decidedly positive. Unlike the inept NRC, it had real motivation and smart, experienced inspectors, who knew where the problems lie and what to look for. By sharing information on problems and best practices, it raised standards and avoided nonsensical situations such as led to TMI. 18 months prior to TMI, the Davis-Besse plant experienced essentially the same failure as at Three Mile Island. However, the Shift Supervisor Mike Derivan went against his training, figured out what was happening, and prevented any damage to the reactor. This information was never distributed to the rest of the industry. So the TMI operators did not realize all they had to do was isolate an open safety valve, and TMI would have been a non-event.

But bureaucratic monopolies grow like cancer. INPO now employs some 350 people, and has an annual budget well over $100 million dollars. A plant’s INPO dues are as large as its liability insurance premium. INPO procedures and paperwork require hundreds of people per plant.4 But nobody complains. That would reveal a poor safety culture. It might effect their rating. INPO is ALARA without the R. One result is that fully depreciated nuclear plants, which should have a marginal cost of less than 1 cents per kWh, cannot compete with gas plants that have a fuel cost of 3 cents per kWh.

(2) sets up a barrier to entry. In the long run, we must have competition among the suppliers of nuclear electricity to force the cost of that electricity down. If I’m an upstart who thinks I can sell nuclear power cheaper than an Excelon or Entergy, I can’t just set up shop and offer my power to local coops, undercutting the big guys. I must get insurance. As a practical matter, that means I must get approval from INPO. But INPO is controlled by my competitors. I do not know how the INPO inspectors are going to treat me, especially since I’m the new guy on the block and I’m not really set up to do all the paperwork. Maybe I should go elsewhere.

INPO guarantees that American nuclear power will be far too expensive to contribute in a meaningful way to the country’s wealth and health or to reducing green house gas emissions. But INPO is a logical, if not inevitable, response to the combination of the Price Anderson suicide pact and the American tort system.

The Only Way Out

The only solution is a fixed compensation scheme with each plant being responsible for its own liability insurance. If a compensation scheme, based only on the dose profile each individual and business would have incurred assuming no evacuation, is combined with a radiation-harm model that recognizes our bodies’ ability to repair radiation damage within limits, the risk will be easily insurable.

As an exercise, the the Sigmoid No Threshold (SNT radiation harm model was applied to the Chernobyl release, excluding the childhood thyroid cancers, which could have been avoided by control of contaminated food. See Why Nuclear Power has been a Flop, Table 6.15. At $350 per lost life day, the public (non-liquidator) compensation came to about $130 million dollars.\cite{flop3}[Table 6.15] From a strictly radiation point of view, this is almost certainly over-compensation. 30 years after the release, the Harvard Medical School found no statistical difference between the cancer incidence in the Ukraine districts adjacent to Chernobyl and those far away.\cite{leung-2019}

These calculations show that an SNT-like compensation scheme, combined with reasonable buffer zones and control of contaminated food, would be feasible. A cap of 500 million dollars would almost never be exceeded. The insurance market is already happily and very profitably writing nuclear liability coverage for 500 million. According to the underwriters, there’s plenty of appetite for more. Each plant can and should be responsible for its own insurance. That way if the underwriting market is unhappy with the way a plant is performing, the insurance will be yanked, and the plant shut down. The good plants will be unaffected. Once such a scheme is implemented, the federal government can leave it up to the underwriters and the locals to regulate nuclear power.

——————————-

1 In a way, the NRC is right. In a competitive market, insurers pay out in claims about what they collect in premia. They make most of their profit on the investment returns from the period during which they control that money. If nuclear plants could go directly to the insurance markets, the premia would be a lot more reasonable. 0.1 cents/kWh for the marginal insurance is a gargantuan ripoff.

2 It’s ironic that the real victims of the tsunami, many of whom lost members of the family and their homes, were left to fend for themselves; while the artificial victims were paid $1000 per person per month to stay away from their undamaged homes. Most of the area around Fukushima Daiichi is reasonably well protected from tsunamis, since the shoreline bluff is about 30 meters high. At Fukushima Daiichi, they excavated this bluff down to 10 meters. This was done to make it easier to get large, vessel delivered components up to the plant, and cut the cost of pumping seawater through the condensers.

3 INPO’s individual plant evaluations are confidential; but, if INPO is aware of any violation of a NRC regulation, and the plant does not report it to the NRC as required, INPO will.

4 This cost like the NRC insurance requirement is pretty much size independent. SMR promoters rarely point this out. INPO has been awarded tax free status on the grounds that it is a charitable organization that relieves “the burden of government”.